Today, the Partner at globally renowned architectural firm Foster + Partners looks back almost quizzically at his years of indecision, remembering clearly that during his studies at Auckland University he wasn’t too enthralled by the idea of designing buildings.

In fact, it was a future which left him feeling underwhelmed – a rather delicious irony considering his input later into some of the world’s most iconic landmarks. “It’s true, while I was studying, I didn’t feel like I really wanted to do architecture,” he admits.

“I wasn’t that passionate about it at the time. It wasn’t like it was something that drove me.” “But then I graduated and it was like, ‘Hang on, there are some things I haven’t done, there are more things I want to make and experiment with. Maybe I can do more.’ So you could say I was a late bloomer.”

Not only did Young’s light-bulb moment propel him into the industry, he went on to do his Masters in Architectural Design in Peter Cook’s Studio at University College London. Fast-forward two decades and it’s abundantly clear there was much more Young could do. His portfolio of projects is as varied as it is impressive.

Think Beijing Capital International Airport, his first major project; Saudi Arabia’s 453-kilometre Haramain high-speed railway and Jordan’s Queen Alia International Airport.

That’s in addition to the multiple designs he’s working on now, including Xiamen Airlines’ new headquarters in Xiamen; a mixed-use tower in Auckland; Goldsun HQ in Taipei; Hengli HQ in Suzhou; a residential-retail development for Gree in Zhuhai; and an island masterplan for Pingan in Dongguan.

There’s also five in Shenzhen, China’s new urban destination: the Guangming Hub; China Merchants Bank’s Global HQ; Sany Creative Technology Park; Nanshan Technology and Financial City; and DJI’s HQ twin towers.

It’s safe to say the passion that eluded Young during his student years is now driving him relentlessly to design developments varying from museums to airports, aquariums to luxury hotels, or master plans including technology parks, transport hubs and headquarter towers.

No matter where our teams are located, they don’t feel detached from london hq … We’re all one office and one design.

“I love what I do. I’m really passionate about the whole creative process. Each project I work on is different and each one presents different challenges,” he explains. “I love the interaction with people, my team and my clients. There’s just so much scope to learn, not just from big projects but from small ones.”

Young admits he’s particularly interested in projects emerging from Asia, a region he feels offers unlimited potential for creativity, and where the way of working is vastly different. Even though he was born in Taiwan, his later years were spent studying or working in the UK and New Zealand.

He admits he was shocked when he took on his first job in Asia, mainly by the difference in work culture and the speed with which things are done. “Yes, it’s a very different culture. What you do for work defines who you are in a number of Asian countries,” he says.

“There are subtle differences, such as the way technology is used, or the different ways to communicate, but the fundamental difference is the boundary between life and work.

It’s very blurred and there may be no personal time. Breakfast, lunch, dinner and weekends can all be regarded as work time, which means things get done very quickly and the projects get realised with great speed.

“That is something I had to get used to, and I guess it’s rubbed off in a way. I do choose to do as much as I can so I can really contribute, and yes, that means sometimes I can find it very difficult to separate life from work. It has become a way of life.”

While Young is mostly absorbed in larger international projects these days, he remembers his first job fondly. After completing his master’s degree, he joined Keith Williams Architects in London in 2001, a smaller office with unique cultural projects. “Theatres, libraries and museums. Many of them got built as well,” he says.

“It was very hands-on; you were the designer, the quantity surveyor, the admin person, so you learned a lot. It was very interesting, very tangible, and something I could control.”

However, Young says he was always hankering for one of those special “once-in-a-lifetime” projects, to build something big, an iconic structure recognised around the world and used by millions.

He wanted to challenge himself when he heard that Foster + Partners was bidding to complete an additional terminal for the Beijing Capital International Airport in time for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The colossal expansion, incorporating 99 hectares of floor space and a total area of 1.3 million square metres, included a rail link to the city centre, and would be the largest airport terminal in the world and the busiest in Asia.

Young wanted to be a part of it, and in 2003 he applied to be on the architectural team. After an interview in the London Riverside HQ, he was offered the job straight away. “I’d always dreamed of working in China,” he recalls.

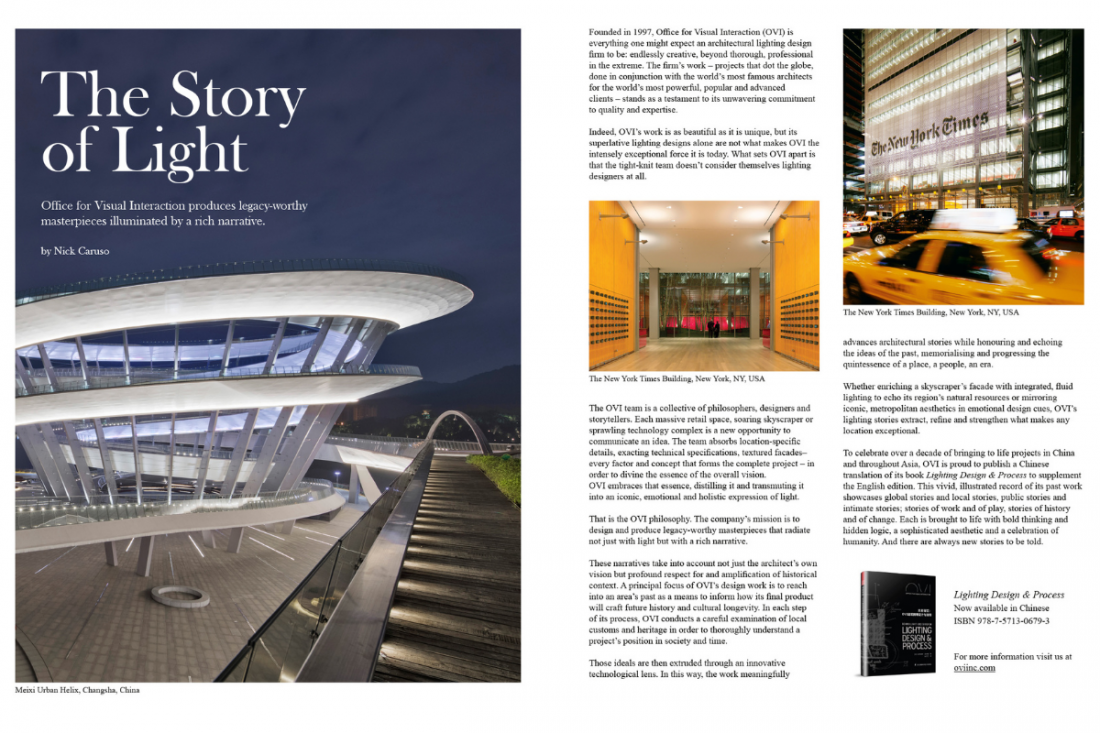

Design Project: DJI Headquarters

The new headquarters for DJI, the world’s leading robotics company, is located in Shenzhen’s Xili District. Spread across twin towers, the headquarters are set to be the ‘heart of innovation’ for the company, defying the traditional idea of office spaces to form a creative community in the sky. At ground level, the podium features a series of gardens that draws the surrounding greenery into the site. The office and research spaces in the two towers above are arranged in floating volumes cantilevered from central cores by large megatrusses. The innovative suspension structure reduces the need for columns, thus creating impressive and uninterrupted office and research spaces. It also allows for quadruple-height drone flight testing labs that are unique to DJI, while giving the towers their distinctive identity against the backdrop of the city’s skyline. Located on the top of the floating volumes, the skygardens provide private gardens for the DJI staff to enjoy. The towers are linked by a feature sky bridge which, along with the skygardens, will become another platform for showcasing the latest drone technology.

“Asia was taking off at the time and the Beijing airport was the biggest project, so I went for it. I was thrown into the deep end, starting with the toughest job. Because it was such a large project and so diverse, there were so many talented people I knew I could learn from. I was working on the external appearance, the roof and the ceiling – the things you’d see, those first impressions.”

Those first impressions included tapered red pillars supporting a soaring brown-gold aerodynamic roof shaped like the back of a dragon. Despite its being one of the largest developments in the world at the time, it was designed and completed within three-anda-half years, an extraordinary speed which Young attributes once again to the culture.

“We opened in time for the Olympics and it was a huge success,” he smiles. “For me, it’s an incredible feeling flying into that airport. I still feel very proud. The airport is part of me and I’m part of the airport. All the late nights and many weekends working were worth it. Since then, our portfolio of projects in Asia grew into many typologies in all major cities.”

Young says that when he first started at Foster + Partner, he was pleasantly surprised to discover it encouraged designers to explore their ideas freely. He says there was no limit to creativity and that concepts, no matter how “radical” they seemed, were welcomed.

“When I joined Foster + Partner I thought there would be a lot of design restrictions in terms of policies and protocols or things you have to adhere to,” Young says. “Instead, I found the opposite. It’s a place where architects have the freedom and flexibility to jump in and develop designs to their full potential.”

Headquartered in London, Foster + Partners shares its expertise around the world, employing more than 1,500 people in a dozen offices worldwide in the UK, UAE, Europe, the US, Australia and Asia, including four offices in mainland China and Hong Kong.

The company was founded in 1967 by English architect Lord Norman Foster, renowned for his innovative designs, including Berlin’s Reichstag, New York City’s Hearst Tower, London’s City Hall and more recently, California’s Apple Park and Bloomberg’s London HQ.

Regarded as one of the most prolific British architects of his generation, the Executive Chair has been an inspiration to scores of other architects around the world, including Young. “When I started at the company, I used to sit a few seats from him so I saw him on a regular basis,” he says.

“He provided us with so much motivation to explore design, and instilled a culture that questions every possibility.” Young certainly has a lot of projects to show off. Although based in London, the projects are global, so they can be worked on virtually 24/7 by the firm’s offices around the world.

“No matter where our teams are located, they don’t feel detached from the London HQ. We are connected through constant calls, video conferences, social media and regular face-to-face meetings – we’re all one office and one design,” he says, speaking from personal experience being involved in setting up a Madrid project office and the newest global office addition in Shenzhen.

He says the common thread among staff is design excellence driven by the best talent. Among the 1,000-plus people in the London office, there are 70 different nationalities speaking 50 different languages.

“We tap into talent from all over the world,” Young says. “We are in touch with most of the major educational institutes internationally, and have strong relationships with tutors. We ensure we get the best graduates every year so we stay ahead.”

Prior to COVID-19, Young was travelling frequently to Asia, visiting various cities to maintain a face-to-face relationship with the teams working on his projects.

Our portfolio of projects in asia grew into many typologies in all major cities.

He says while technology obviously makes working around the world easier, and having worked remotely on projects for years, he still regards personal collaboration as vitally important, particularly with clients.

“I like to get a feel for how our clients work, and personal meetings give our clients an understanding of what we do,” he reveals. For most of last year, with COVID-19 restrictions enforced, Young worked from his home in central London.

While conceding the luxury of having a spare room to set up office, he describes the experience as triggering an intensity not felt before.

“It always seems a lot busier,” he reflects. “I think it’s because before you could avoid all those office meetings and calls you were expected to have. You could be out visiting a site or a client. When you’re in lockdown you’ve got no excuse, you can join a meeting from anywhere, you can’t hide from an online meeting.

“Even post-COVID-19, when we’re all back working in the offices, I think some aspects of travel will not be necessary any more. People have become very used to the technology of online meetings and collaboration. But for some clients, face-to-face communication will never be replaced.”

Constantly working on multiple projects, aiming to allocate “as much time as it needs” to each development every day, Young says the speed with which Asia works in particular is a great attribute because this makes it possible to complete several projects in just a few years, compared with more established markets, in which projects could take much longer to complete.

He says he’s proud of all of his projects, and while he denies having a favourite, he concedes there are some that demand more time, energy and passion.

A large part of the commitment depends on the relationship built with the client, and Young says it’s vital to get to know the client well so when there are differences of opinion in design, the problem can be successfully managed.

While it’s not easy when clients don’t appreciate the reasoning behind an architect’s vision, it’s just as tricky when clients don’t understand why their suggestions can’t be implemented. “It’s never a one-sided affair and ultimately, of course, we’re designing projects and buildings for other people, our clients,” Young insists.

“You may have a client really interested in the design, another who wants to challenge you, or sometimes it’s just a case of the client never having been exposed to a particular idea. It’s educational in both directions – you can learn a lot from clients, and they can learn a lot from you.

It’s a case of working together to find the right solutions. As architects, however, we have a responsibility to do what’s right, especially these days when buildings consume so much of our resources and sustainable outcomes are a priority.

We have teams of different people who can help to substantiate our story for an idea. In fact, I think we have a lot of support compared with other practices.

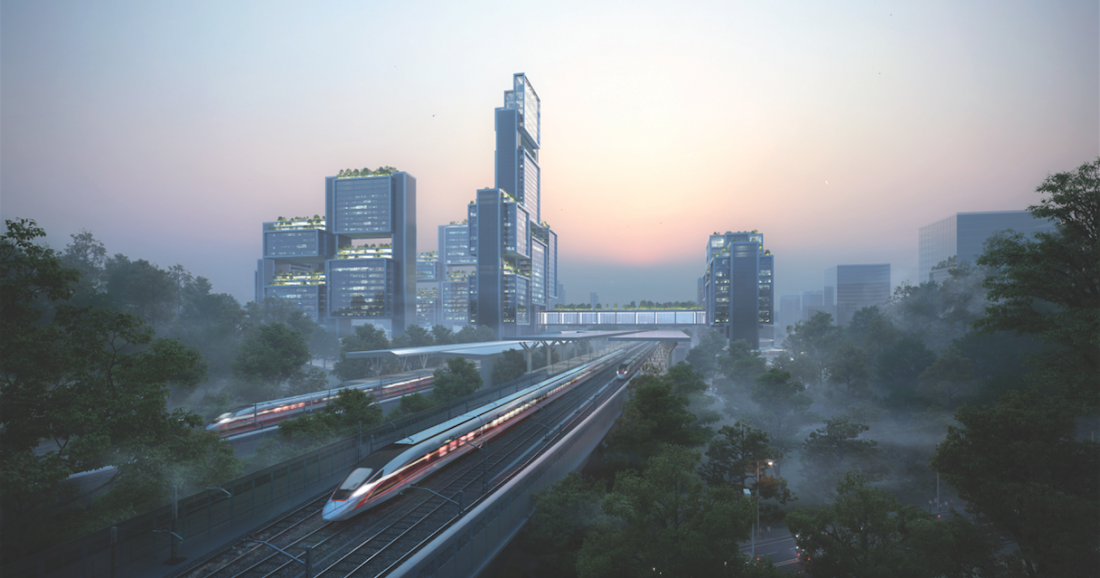

Design Project: Guangming Hub

In November last year, Foster + Partners unveiled its winning design for the Guangming Hub, a transport-oriented development located on the existing high-speed rail station that connects the cities of Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. The proposal, the focal point of a new masterplan for the region, integrates three new metro lines in the city and will feature skybridges and shared surfaces for cyclists and pedestrians. Using the latest technology, Foster + Partners is creating a smart city to encourage the flow of people and goods with the support of powerful infrastructure, effective transport networks, reliable public services and generous lush greenery.

“Apart from our experts in research, urban design, structure and MEP engineering, we also have a specialised virtual modelling department, a physical model shop, environmental engineers, space scientists, mathematicians, scripters, anthropologists, product designers, landscapers, lighting experts, space planners, artists, musicians and economists – different people offering different skills who collaborate with us to come up with something really innovative.”

Young says a priority with contemporary architecture today is “futureproofing” buildings, which means ensuring designs are flexible enough to be altered when circumstances change.

Using airports as an example, he points out that internal layouts have changed significantly over the past two decades as check-in counters are replaced by machines. Security advances are also being made with new technology.

“Our workspace is also evolving as different industries grow, attracting a varied demographic trend in the workforce,” Young says.

“We see the change not just in the technology, but the psychology is also changing. In order not to be wasteful with our buildings in the future, we need to be able to analyse and forecast the user behaviour. Buildings need to have the ability to be flexible to survive, not rigid. They need to be able to adapt so they don’t become obsolete. One way this can be enabled is by having an open, flexible floor plate that allows you to change the function of the space to accommodate changing needs.

“Cruise terminals that are seasonal are another example. In summer they’re very busy, but in winter they’re less so. So we need to design the building to be used as a terminal when needed, but also as a multi-functional place for exhibitions or banquets at other times. After all, cruise terminals often have the best views overlooking the water.

“If we can minimise waste in the way the spaces are used by people, we will save energy. We can achieve a more sustainable future together with recycling, utilisation of renewables, and construction methods to reduce embodied energy.”

Young adds that to create a presentation, tossing around ideas with team members or clients is hard work but often the “fun part”, describing it as almost like directing a movie where a strong beginning and a spectacular ending are required.

“Yes, it’s almost like being a director,” he concedes. “To get them to buy into the concept, you’re coming up with narratives for the building, drawing up a storyboard, directing a movie, to show clients the ideas behind your design and where it’s all going. That is the best part of the work.” As for finding fun outside the work Young is so passionate about, he relies on a combination of exercise and relaxation. On weekends you can usually find him at the basketball court, or by the river with a rod in hand. “I used to play a lot of basketball, so I try to do that with friends,” he says.

“I also like to fish, catch and release. It’s a great way to switch focus.” Meanwhile, firm in his belief that “the more you do, the more valuable you are”, Young says Foster + Partners provides an excellent training ground for young, emerging architects.

Not only does the company offer all the necessary design tools and resources, but it also invests more in innovation and testing different design solutions.

Indeed, he’s living proof of this, having collaborated on an extraordinary variety of projects from airports in Beijing to super-tall towers in the Middle East and a house in Japan.

“Design excellence is at the forefront of Foster + Partners. Creating designs that are functional, beautiful and sustainable is above all the considerations,” Young enthuses. How do they continue to support this nonstop pursuit of perfection?

“We have to get the right talent,” he says. “How do we retain that talent? We provide the right environment and opportunities to enable them to grow.”

Proudly supported by:

GDAD

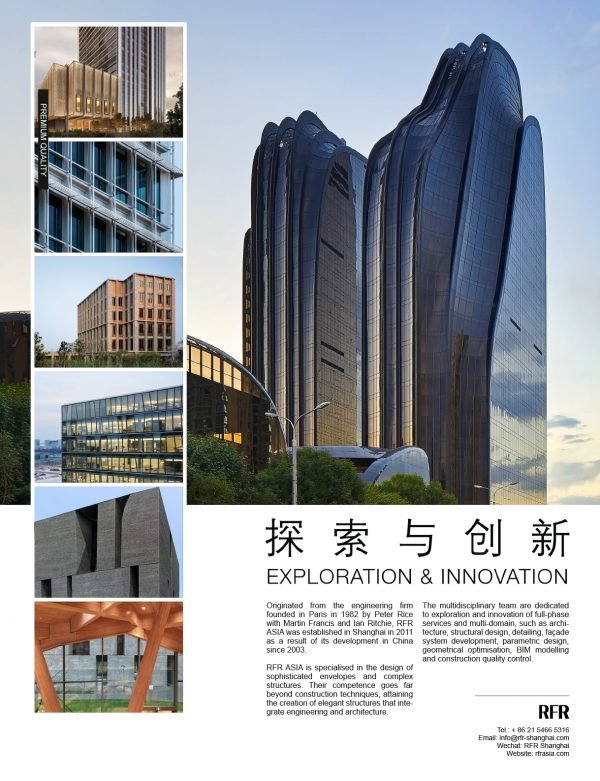

RFR

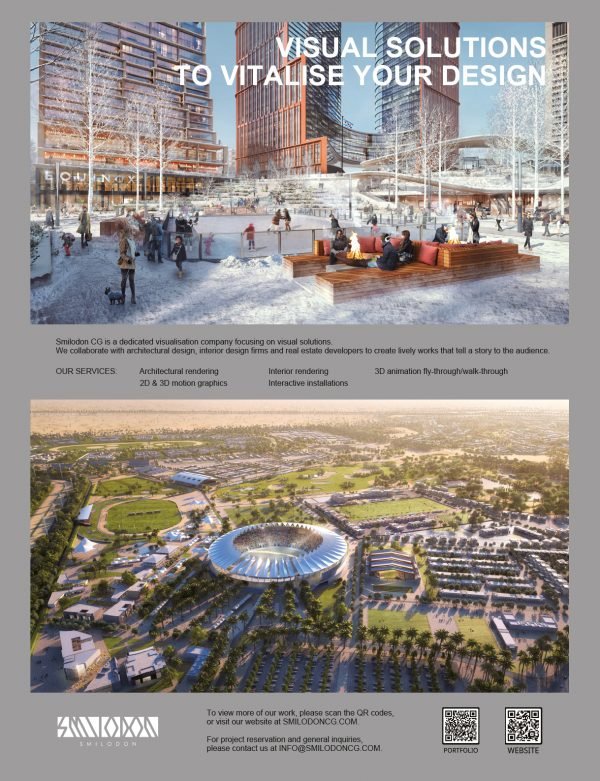

Smilodon